Whenever they can, Charles Aubry and his wife watch the show My 600 Lb Life.

While reflecting on the collision shop industry, Charles draws a parallel between the drama around the show’s subjects and shops that maintain excessive work-in-progress (WIP) loads. He calls it “My life with a 600-hour WIP.”

He explains why, and get this, it makes sense.

First, what are the negative consequences of maintaining a very high WIP?

- Higher operational costs, for example with the use of replacement vehicles.

- Lower cash-flow, mainly because of money monopolized for purchasing parts that just sit while waiting to be installed.

- Lower performance in terms of profitability and cycle time.

- The shop becomes greedier, the costs are higher, so more repairs are needed to be profitable.

- Less desirable customer experience.

- Reports to insurance partners show significant weaknesses in the workshop.

We can ask ourselves; is my workshop suffering from morbid obesity?

You can verify this with the following two exercises:

Exercise 1—Assess your shop’s work in progress.

Simply walk around the shop and count the number of vehicles to be repaired. Let’s say there are 12.

Multiply this number by the average repair time according to the season: 17 hours in the summer, 20 hours in fall and spring and 25 hours in the winter.

Let’s say it’s November 22 (fall), you’ll need to multiply the 12 vehicles by 20 hours, which gives 240 hours.

But on February 14 (winter), 12 vehicles waiting in the yard or being repaired in the shop will represent 300 hours.

Of course, for classic business models, the season can greatly affect the shop’s workload, and you will generally be busier in winter than in summer.

Exercise 2—Assess what the perfect WIP should be to avoid the negative consequences of an overloaded shop.

- Identify your number of productive employees and multiply it by the number of repair hours per week per employee (e.g.: 5 productive employees × 35 h = 175).

- Multiply by your productivity level. If you don’t know it, use 100% (a ratio of 1) (e.g.: 175 ×1 = 175).

- Divide by 5 days, or the number of days you work in a week (e.g.: 175/5 = 35).

In the example above, the WIP is 35 hours. To fill your next working day, your WIP at the end of each day should be equivalent to 35 hours (give or take 10%) plus the hours for non-drivable vehicles.

The goal is for the WIP to be as close as possible to what you can achieve in a working day.

Perfect WIP = The work you can accomplish in a day (give or take 10%), without considering the non-drivable vehicles.

If the gap between your current WIP and a perfect WIP is too big, you must ask yourself how you got there. In Charles’s favourite show, people all have tragic stories to tell why they weigh 600 lb.

Try to tell yourself your own story to see what managerial behaviours make you accumulate so many repairs. These are the behaviours that you will need to change to achieve higher performance and profitability in your shop.

A Major Impact on Profitability

Let’s take two shops with the same sales mix, team size, fixed costs and organized in much the same way. One generates 5% profitability and the other 15%. Yet, both workshops are very productive yielding over 70 estimated work hours per technician per week. One has a huge WIP and the other maintains its WIP as LEAN as possible. What distinguishes them is profitability and success. So, the WIP should not be taken lightly.

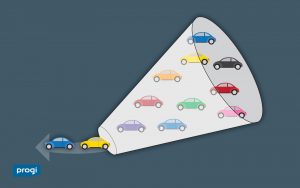

Imagine that you are the last customer to arrive at the shop shown in image B.

- IMAGE A

- IMAGE B

How confident would you be that you would get your vehicle back within an acceptable timeframe?

A 600-hour WIP (it’s all relative depending on the size of the workshop), is as alarming as if you weighed 600 lb. The damage to profitability is as serious as the damage to people’s health.

What is the magic formula for maintaining a healthy WIP? Get organized, use a good tool to track repairs and plan repair appointments at the right time, and finally deliver and receive vehicles every day.

Author: Alexandre Rocheleau

Collaboration: Charles Aubry

Translation: Sophie Larocque

Illustration: Paul Berryman

Editing : Emilie Blanchette